Frida 16.3.0 Released ∞

release

This release is packing some exciting new things. Let’s dive right in.

CoreDevice

Starting with iOS 17, Apple moved to a new way of communicating with services on the iDevice side, including their Developer Disk Image (DDI) services. Their new way of doing things unifies how Apple software talks to other Apple devices, and is known as CoreDevice. It seems to have originated back when Apple introduced their T2 coprocessor. Cisco’s DUO team published some excellent research on this back in 2019.

Like with the T2, the new stack used for iOS also uses RemoteXPC for talking to services. Things are a bit more complex though, because unlike the T2, mobile devices don’t have a persistent connection to macOS, and also have the notion of pairing. Luckily for us, @doronz88 had already done an amazing job reversing and documenting most of what we needed to implement the new protocols, so that saved us a lot of time.

Even so, it was a massive undertaking, but tons of fun – @hsorbo and I had a blast pair-programming on it. Quite a few moving parts are involved, so let’s take a quick walk through them.

With an iDevice plugged in, it exposes a USB CDC-NCM network interface, known as the “private” interface. It also exposes an interface used for tethering, just like it did in the past – except back then it was using a proprietary Apple protocol instead of CDC-NCM.

This is where we hit the first challenges trying to talk to it from a Linux

host. First off, the iOS device needs a USB vendor request to mode-switch it

into exposing the new interfaces. This part is easy, as the usbmuxd daemon can

do this for us if we set the environment variable USBMUXD_DEFAULT_DEVICE_MODE

to 3. So far so good.

The next challenge was that the Linux kernel’s CDC-NCM driver failed to bind to the device. After a bit of debugging we discovered that it was due to the private network interface lacking a status endpoint. The status endpoint is how the driver gets notified about whether a network cable is plugged in. Apple’s tethering network interface has such an endpoint, and it makes sense there – if tethering is disabled it’s just as if the cable is unplugged. But the private interface is always there, so understandably Apple chose not to include a status endpoint for it.

We quickly developed a kernel driver patch to lift the requirement for a status endpoint, and this got it working. Later we realized that we should still require a status endpoint for the tethering interface, so we ended up refining our patch a bit further. The plan is to submit that in the next few days.

Anyway, with the network interface up, the host side uses mDNS to locate the IPv6 address where a RemoteServiceDiscovery (RSD) service is listening. The host connects to it and speaks HTTP/2 with RemoteXPC messages going back and forth. This particular service, RSD, tells the host which services are available on the private interface, the port numbers they’re listening on, and details like the protocol each uses to communicate.

Then, knowing which services are listening on which ports, the host looks up the Tunnel service. This service lets the host establish a tunnel to the device, acting as a VPN to allow it to communicate with the services inside that tunnel. Since setting up such a tunnel requires a pairing relationship between the host and the device, it means that the services inside the tunnel allow the host to do a lot more things than the services outside the tunnel.

The base protocol is the same as with RSD, and after some back and forth involving a pairing parameters binary blob and some cryptography, a pairing relationship is either created or verified. At this point the two endpoints are using encrypted communications, and the host asks the Tunnel service to set up a tunnel listener.

Now, assuming the host asked for the default transport, QUIC, the host goes ahead and connects to it. We should note that the the Tunnel service also supports plain TCP. Presumably that is there for older macOS versions that don’t come with a QUIC stack. Another thing worth mentioning is that the Tunnel service provides the host with a keypair, so it uses that as part of the connection setup.

Once connected, the device sends the host some data across a reliable stream. The data starts with an 8 byte magic, “CDTunnel”, followed by a big-endian uint16 that specifies the size of the payload following it. The payload is JSON, and tells the host which IPv6 address the host’s endpoint inside the tunnel has, along with the netmask and MTU. It also tells the host its own IPv6 address inside the tunnel, and the port that the RSD service is listening on.

The host then sets up a TUN device configured as it was just told, and starts feeding it unreliable datagrams as they’re received from the QUIC connection. And for data in the other direction, whenever there’s a new packet from the TUN device, the host feeds that into the QUIC connection.

So at this point the host connects to the RSD endpoint inside the tunnel, and from there it can access all of the services that the device has to offer. The beauty of this new approach is that clients communicating with device-side services don’t have to worry about crypto, nor provide proof of a pairing relationship. They can simply make plaintext TCP connections on the tunnel interface, and QUIC handles the rest transparently.

What’s even cooler is that the host can establish tunnels across both USB and WiFi, and because of QUIC’s native support for multipath, the device can seamlessly move between wired and wireless without disrupting connections to services inside the tunnel.

So, once we got all of this implemented we were feeling excited and optimistic. Only part left was to do the platform integrations. And uhh yeah, that’s where things got a lot harder. The part that got us stuck for a while was on macOS, where we realized we had to piggyback on Apple’s existing tunnel. We discovered that the Tunnel service would refuse to talk to us when there’s already a tunnel open, so we couldn’t simply open up a tunnel next to Apple’s.

While we could ask the user to send SIGSTOP to remoted, allowing us to set up

our own tunnel, it wouldn’t be a great user experience. Especially since any

Apple software wanting to talk to the device then wouldn’t be able to, making

Xcode, Console, etc. a lot less useful.

It didn’t take us long to find private APIs that would allow us to determine the device-side address inside Apple’s tunnel, and also create a so-called “assertion” so that the tunnel is kept open for as long as we need it. But the part we couldn’t figure out was how to discover the device-side RSD port inside the tunnel.

We knew that remotepairingd, running as the local user, knows the RSD port,

but we couldn’t find a way to get it to tell us what it is. After lots of

brainstorming we could only think of impractical solutions:

- Port-scan the device-side address: Potentially slow, and faster implementations would require root for raw socket access.

- Scan

remotepairingd’s address space for the device-side tunnel address, and locate the port stored near it: Wouldn’t work with SIP enabled. - Rely on a device-side frida-server to figure things out for us: This wouldn’t work on jailed iOS, and would be complex and potentially fragile.

- Grab it from the syslog: Could take a while or require a manual user action, and forcing a reconnection by killing a system daemon would result in disruption.

- Give up on using the tunnel, and move to a higher level abstraction, e.g. use MobileDevice.framework whenever we need to open a service: Would require us to possess entitlements. Exactly which depend on the particular service. So for example if we’d want to talk to com.apple.coredevice.appservice, we’d need the com.apple.private.CoreDevice.canInstallCustomerContent entitlement. But, trying to give ourselves a com.apple.private.* entitlement just wouldn’t fly, as the system would kill us as only Apple-signed programs can use such entitlements.

This was where we decided to take a break and focus on other things for a while,

until we finally found a way: The remoted process has a connection to the RSD

service inside the tunnel. We finally arrived at a simple solution, using the

same API that Apple’s netstat is using:

foreach (var item in XNU.query_active_tcp_connections ()) {

if (item.family != IPV6)

continue;

if (!item.foreign_address.equal (tunnel_device_address))

continue;

if (Darwin.XNU.proc_pidpath (item.effective_pid, path_buf) <= 0)

continue;

if (path != "/usr/libexec/remoted")

continue;

try {

var connectable = new InetSocketAddress (tunnel_device_address, item.foreign_port);

var sc = new SocketClient ();

SocketConnection connection = yield sc.connect_async (connectable, cancellable);

Tcp.enable_nodelay (connection.socket);

return yield DiscoveryService.open (connection, cancellable);

} catch (GLib.Error e) {

}

}The Linux side of the story was a lot easier though, as there we are in control and can set up a tunnel ourselves. There was one challenge however: We didn’t want to require elevated privileges to be able to create a tun device. The solution we came up with was to use lwIP to do IPv6 in user-mode. As we had already designed our other building blocks to work with GLib.IOStream, decoupled from sockets and networking, all we had to do was implement an IOStream that uses lwIP to do the heavy lifting. Datagrams from the QUIC connection get fed into an lwIP network interface, and packets emitted by that network interface are fed into the QUIC connection as datagrams.

Next up was the Windows side of things. We did some digging and quickly realized that Apple’s software doesn’t currently set up a tunnel. The official driver also appears to keep the USB device busy, meaning we can’t easily trigger a mode-switch and do things ourselves. There’s probably an elegant solution to the Windows part of the puzzle, but we realized we were already so deep inside the rabbit-hole that it would be wise to leave this for later. So if anyone reading this is interested in helping out, please do get in touch.

Another area that needs future improvement is that we only support cabled connectivity on macOS. This should be easy to improve on once we have updated frida-server and frida-gadget so they listen on tunnel interfaces whenever they appear.

Jailed iOS 17

With the new CoreDevice infrastructure in place, we have also restored support for jailed instrumentation on iOS 17. This means we can once again spawn (debuggable) apps on latest iOS, which is 17.5.1 at the time of writing. We still have the issue where attach() without spawn() doesn’t work, as our jailed injector doesn’t yet support the restartable dyld case when attaching to an already running app. This will be addressed in a future release.

Device.open_service() and the Service API

Given that Frida needs to speak quite a few protocols to interact with Apple’s device-side services, and applications also sometimes need other such services, this presents a challenge. Applications could speak these protocols themselves, e.g. after using the Device.open_channel() API to open an IOStream to a specific service. But this means they have to duplicate the effort of implementing and maintaining the protocol stacks, and for protocols such as DTX they may be wasting time establishing a connection that Frida already established for its own needs.

One possible solution would be to make these service clients public API and expose them in our language bindings. We would also have to implement clients for all of the Apple services that applications might want to talk to. That’s quite a few, and would result in the Frida API becoming massive. It would also make Frida a kitchen sink of sorts, and that’s clearly not a direction we want to be heading in.

After thinking about this for a while, it occurred to me that we could provide a generic abstraction that lets the application talk to any service that they want. So last week @hsorbo and I filled up our coffee cups and got started on just that.

Here’s how easy it is to talk to a RemoteXPC service from Python:

import frida

import pprint

device = frida.get_usb_device()

appservice = device.open_service("xpc:com.apple.coredevice.appservice")

response = appservice.request({

"CoreDevice.featureIdentifier": "com.apple.coredevice.feature.listprocesses",

"CoreDevice.action": {},

"CoreDevice.input": {},

})

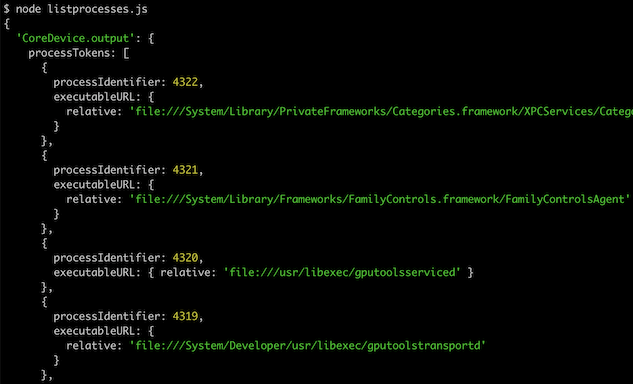

pprint.pp(response)And the same example, from Node.js:

import frida from 'frida';

import util from 'util';

const device = await frida.getUsbDevice();

const appservice = await device.openService('xpc:com.apple.coredevice.appservice');

const response = await appservice.request({

'CoreDevice.featureIdentifier': 'com.apple.coredevice.feature.listprocesses',

'CoreDevice.action': {},

'CoreDevice.input': {},

});

console.log(util.inspect(response, {

colors: true,

depth: Infinity,

maxArrayLength: Infinity

}));Which results in:

So now that we’ve looked at the new open_service() API being used from Python and Node.js, we should probably mention that it is (almost) just as easy to use this API from C:

#include <frida-core.h>

int

main (int argc,

char * argv[])

{

GCancellable * cancellable = NULL;

GError * error = NULL;

frida_init ();

FridaDeviceManager * manager = frida_device_manager_new ();

FridaDevice * device = frida_device_manager_get_device_by_type_sync (manager, FRIDA_DEVICE_TYPE_USB, -1, cancellable, &error);

FridaService * service = frida_device_open_service_sync (device, "xpc:com.apple.coredevice.appservice", cancellable, &error);

GVariant * parameters = g_variant_new_parsed ("{"

"'CoreDevice.featureIdentifier': <'com.apple.coredevice.feature.listprocesses'>,"

"'CoreDevice.action': <@a{sv} {}>,"

"'CoreDevice.input': <@a{sv} {}>"

"}");

GVariant * response = frida_service_request_sync (service, parameters, cancellable, &error);

gchar * str = g_variant_print (response, FALSE);

g_printerr ("%s\n", str);

return 0;

}(Error-handling and cleanup omitted for brevity.)

The string passed into open_service() is the address where the service can be

reached, which starts with a protocol identifier followed by colon and the

service name. This returns an implementation of the Service interface, which

looks like this:

public interface Service : Object {

public signal void close ();

public signal void message (Variant message);

public abstract bool is_closed ();

public abstract async void activate (Cancellable? cancellable = null) throws Error, IOError;

public abstract async void cancel (Cancellable? cancellable = null) throws IOError;

public abstract async Variant request (Variant parameters, Cancellable? cancellable = null) throws Error, IOError;

}(Synchronous methods omitted for brevity.)

Here, request() is what you call with a Variant, which can be “anything”,

a dictionary, array, string, etc. It is up to the specific protocol what is

expected. Our language bindings take care of turning a native value, for example

a dict in case of Python, into a Variant. Once request() returns, it gives you

a Variant with the response. This is then turned into a native value, e.g. a

Python dict.

For protocols that support notifications, the message signal is emitted

whenever a notification is received. Since Frida’s APIs also offer synchronous

versions of all methods, allowing them to be called from an arbitrary thread,

this presents a challenge: If a message is emitted as soon as you open a

specific service, you might be too late in registering the handler. This is

where activate() comes into play. The service object starts out in the

inactive state, allowing signal handlers to be registered. Then, once you’re

ready for events, you can either call activate(), or make a request(), which

moves the service object into active state.

Then, later, to shut things down, cancel() may be called. The close signal

is useful to know when a Service is no longer available, e.g. because the

device was unplugged or you sent it an invalid message causing it to close the

connection.

It’s also easy to talk to DTX services, which is RemoteXPC’s predecessor, still used by many DDI services.

For example, to grab a screenshot:

import frida

device = frida.get_usb_device()

screenshot = device.open_service("dtx:com.apple.instruments.server.services.screenshot")

png = screenshot.request({"method": "takeScreenshot"})

with open("/path/to/outfile.png", "wb") as f:

f.write(png)But there’s more. We also support talking to old-style plist services, where you send a plist as the request, and receive one or more plist responses:

import frida

device = frida.get_usb_device()

diag = device.open_service("plist:com.apple.mobile.diagnostics_relay")

diag.request({"type": "query", "payload": {"Request": "Sleep", "WaitForDisconnect": True}})

diag.request({"type": "query", "payload": {"Request": "Goodbye"}})As you might have already guessed, this example puts the connected iDevice to sleep.

RPC Binary Passing

Those of you using Gum’s JavaScript bindings might be familiar with our RPC API, which makes it easy for an application to call functions on its agent.

One long-standing limitation with this feature was that you couldn’t pass binary data into an exported function – you would have to serialize it somehow. This is now finally supported.

For example given the following agent:

rpc.exports.hello = (name, icon) => {

console.log(`Name: "${name}"`);

console.log('Icon:');

console.log(hexdump(icon, { ansi: true }));

};You can now call hello() from Python like this:

script.exports_sync.hello("Joe", b"\x13\x37")Which would output:

Note that only one binary parameter can be passed, and it needs to be the last parameter.

Another improvement in the same area is that you can now return binary data alongside a JSON-serializable JavaScript value. We previously only supported returning one or the other. This is now also finally supported.

For example given the following agent:

rpc.exports.peek = name => {

const module = Process.getModuleByName(name);

const header = module.base.readByteArray(64);

return [module, header];

};You can call peek() from Python like this:

module, header = script.exports_sync.peek("libSystem.B.dylib")

print("module:", module)

print("header:", header)Which, if run on a platform where libSystem.B.dylib is present, might output something like:

module: {'name': 'libSystem.B.dylib', 'base': '0x18ec70000', 'size': 8192, 'path': '/usr/lib/libSystem.B.dylib'}

header: b'\xcf\xfa\xed\xfe\x0c\x00\x00\x01\x02\x00\x00\x80\x06\x00\x00\x006\x00\x00\x00\x10\x10\x00\x00\x85\x00\x00\x82\x00\x00\x00\x00\x19\x00\x00\x00(\x02\x00\x00__TEXT\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00@\x0c\x8d\x01\x00\x00\x00'EOF

There’s also a few other exciting changes, so definitely check out the changelog below.

Enjoy!

Changelog

- Add device.open_service(address), which provides a Service implementation that exposes device-specific services through a uniform interface.

- fruity: Add RemoteXPC support, with open_service() implemented for three protocols IDs: plist, dtx, xpc.

- fruity: Fix spawn() on jailed iOS 17.

- fruity: Improve DTX protocol support.

- python: Add open_service() and Service API.

- python: Add support for new RPC binary data passing.

- python: Improve GVariant marshaling support.

- node: Add openService() and Service API.

- node: Add support for new RPC binary data passing.

- node: Improve GVariant marshaling support.

- exceptor: Add SA_ONSTACK flag in the POSIX backend. Thanks @asabil!

- gumjs: Support receiving binary data in RPC methods.

- gumjs: Support returning value and binary data from RPC methods.

- gumjs: Expose more Memory APIs to CModule. Thanks @hillelpinto!

- plist: Fix support for writing out binary plist with float and double values.

Kudos to @hsorbo for the fun and productive pair-programming on all of the above changes without specific attribution! 🙌

oleavr

oleavr